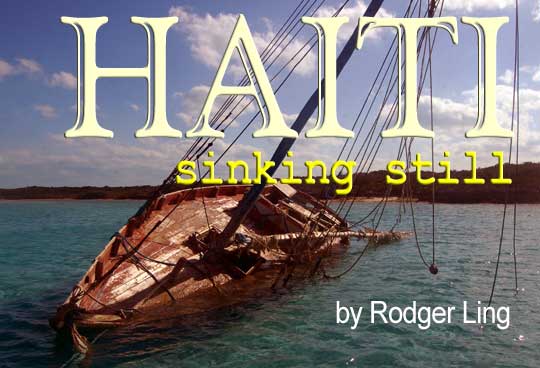

The sunken boat was lying on her side in the shallow water, heeled over as if by the wind. Even from a distance I could see the distinctive lines of a Haitian sailboat, roughly hewn of heavy timbers. I had first spotted her when we came in Dotham Cut from Exuma Sound in the Bahamas, just a mile or so north of Black Point Settlement. Now, several days later, I had come back in the dinghy for a closer look.

We had seen Haitian sailboats in the Turks & Caicos, and the wrecks of Haitian boats throughout the Bahamas. Some were sailing freighters, taking bananas, rice, and especially charcoal up to Nassau. Unfortunately, more than two decades after Haitian "boat people" started taking to the seas, some of these boats are still hauling human cargo. Tom Barbernitz, the ranger at Exuma Park, told me that the park inspects about two Haitian boats a week. About once a month, they find one carrying illegal immigrants--as many as 186 stuffed onto a 40 foot boat. Three weeks ago, a Haitian sailboat with 75 aboard went aground inside the park at Cistern Cay. Like most intercepted boats, the vessel was burned; the people, having risked their lives for nothing, were sent back to Haiti.

Americans are incredibly insulated from the world around them, and cruisers in the Bahamas are no exception. Until we actually touch a place or meet its people, we don't really make a connection. The previous winter we had sailed our 35 foot sloop Seaductress south to the Dominican Republic, literally next door to Haiti, but I never really connected with the country until I climbed out of my dinghy onto that wrecked Haitian boat. A thin sail was still lashed to the boom, the canvas of the jib splayed out in the water ahead of me. The slanted deck felt solid underfoot, the construction crude but surprisingly strong. With some trepidation I looked down into the interior of the boat: roughly planked, flooded but empty except for bags of concrete ballast. The shrouds supporting the mast were old galvanized cable, tied to the boat with salvaged rope, every piece a different color. I couldn't imagine piloting a boat like this one across the open ocean. There would be no engine, no electricity, no instruments, perhaps just a handheld compass for navigation. The most high-tech thing aboard was a plastic pipe coming down through the deck that served as a home-made bilge pump. On one of these vessels, you'd be sailing very much as it was done hundreds of years ago.

If the boat I was standing on had been smuggling immigrants, it obviously hadn't been destroyed. Instead, it look as if that this boat had sunk quietly while at anchor. Many boats carrying human cargo are built and used just once, on a one-way trip north. Could a boat full of Haitians--up to a hundred souls have been packed into a cargo hold this size--have ended their journey here? In the shallow water nearby were the remains of at least two similar vessels. What, exactly, had happened? When I asked Tom, he ventured that sometimes the Bahamas Defense Force tows a boat full of illegals in, then doesn't get around to burning it. Without someone around to pump them out regularly, the boats usually sink within a few days.

Haiti, once the richest nation in the Caribbean, is the poorest country in the western hemisphere. Since declaring independence in 1804, assassinations and coup d’etats have come in an endless parade, one after another. Gangs, death squads, and poverty seem to be the only constants. Eight out of ten Haitians live below the poverty line; most are unemployed. A cruiser who had flown over Haiti told me that you could actually see the border of the two countries: the Dominican Republic side lush and green, the Haitian side deforested and bare. What, I wondered, is America's role in all of this? The United States invaded and occupied Haiti from 1915 until 1934, but maintained "fiscal control" until 1947. In my lifetime, tyrants such as "Papa Doc" and "Baby Doc" Duvalier ruled by terror with the implicit assent of the United States. In 1990, the socialist priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected, then overthrown just seven months later in yet another military coup. The United States returned Aristide to power in 1994: he left office when his original term expired, was reelected in 2001, and then forced out again. The U.S. and the United Nations sent in troops, withdrew them, sent them back.

Like Haiti itself, U.S. policy towards the country has been chaotic, fueled in recent decades largely by our desire to keep Haitian boat people away from our shores. Haiti was President Clinton's first real crisis, and he stumbled through it with mixed signals and outright reversals on sending Haitians back to Haiti. An angry Haitian mob chased away the Harlan County, a United States warship. Despite our efforts (and sometimes because of them), Haitians continued to dream of sailing to a better life, often selling everything they owned and mortgaging their future earnings for the chance to do so. In the three years between 1992 to 1994, the Coast Guard intercepted over 60,000 Haitians trying to flee in small boats. In recent years the number has declined to around 1,500 annually, no doubt due in part to our harsh repatriation policies. Unlike refugees from other countries, Haitians are given few chances to plead their case for asylum. Despite reports of Haitian citizens being killed for putting up campaign posters, of children being decapitated in the streets, the U.S. has argued for years that Haitians are fleeing economic hardship, not political persecution. At the same time, America remains Haiti's greatest single benefactor. The United States donates around $200 million a year to promote stability in Haiti--less than we spend in a single day on Iraq, but it's a start.

I suspect that the majority of Americans, like me, don't pay much attention to Haiti until it smacks us in the face. Since we are sailing the same waters, cruisers occasionally do get smacked. In April of 2000 three cruising boats anchored off Flamingo Cay in the Jumentos found 288 Haitians who had been shipwrecked there, some near death. Just a couple of weeks ago, cruisers happened across two young Haitians clinging to debris from a homemade boat off the Dominican Republic; they were evidently the only survivors of more than fifty who were trying to reach the Turks & Caicos. A few cruisers--make that a very few--seek out Haiti deliberately (see www.travelblog.org/ for a wonderful log and photographs by a cruising couple who have spent much of the past two years in Haiti).

After more than 200 years of almost constant turmoil, there is no quick solution to the Haitian dilemma, no easy answer. Unfortunately, most of us aren't even asking the question. Unless bodies are washing up on our beaches, as they occasionally do in Florida and the Bahamas, we don't even see the problem.

It's as if we live in a parallel universe, a completely different world.

A week after I stepped onto the Haitian boat we are a dozen miles north at Compass Cay Marina, watching a gleaming ninety foot motor yacht depart the docks. The captain is at the controls, surrounded by glowing screens of electronics. The owners are reclining on top of what looks like a big covered hot tub on the rear deck, arranged there like a couple of Greek statues. The yacht's crew do everything from running the boat to putting the flippers on the feet of the owners when they go snorkeling. Engines barely above idle, the boat moves off with a huge rush of water. I wonder: as they glide through paradise, their crew standing by to pour another glass of white wine, would these yachties feel a twinge of conscience if they happened upon a crude wooden boat drifting under sail, a hundred souls staring at them from its deck? But then, am I so different? By Haitian standards, every cruising boat is a mega-yacht, every American a millionaire.

The very next day I am standing on Bitter Guana Cay, our tiny mega-yacht safely anchored a hundred yards off a beautiful beach. Somewhere on this uninhabited island is a mass grave that is as close to the promised land as 39 Haitians were able to get. They drowned below decks in 1990 when their overloaded boat, taken in tow by the Bahamas Defense Force, capsized. Now, almost seventeen years later, I am looking at a large mound of rock, coral fragments, and shells that is obviously man-made. The conch shells in the pile are so old that they look like ancient gray bones. But the site is unmarked, and I am left to wonder as I ride alone back to the boat.

Seaductress rocks in a brisk wind that grows cold as the sun goes down. That night there is no moon and the shoreline, then the island itself, fades away until to my eyes it is almost invisible.

More info on Haiti:

1994 Peter Jennings Special Report

So Many Mis-Steps

BBC Timeline: Haiti

U.S./Haiti Timeline

Haitian Boat People

Desperate Mariners

Coast Guard Alien Migrant Interdiction

Coast Guard Photos

Coast Guard Photos of 30 ft. Sailboat

"Where the Air is Thin"

The subtitle is from an editor Peter Janssen's essay in the November 2006 Yachting magazine, where he lists the cost of a typical 80 footer at $3 million to $4 million, with the price tag rising to $70 million for a 200 foot yacht. Larry Ellison's 452 foot Rising Sun reportedly has 86,000 square feet of living space, "about the same size as the average Walmart." Another article in Yachting describes a week-long charter at Staniel Cay in the Exumas as a bargain at $16,000 for a week, or less than the author usually spent at a golf resort. "There are more than 6,000 superyachts (starting at 80 feet) in the world..." Janssen writes, "and another 651 are under construction."