There are bad trips, and then there are bad trips. The worst caving trip I ever had? That's easy.

There was the night in 1977, on the day of my 16th birthday, that I sat shivering in Lusk Double Pot, waiting for my companions and listening to the illusion of voices in the sounds of the stream. I couldn't help but think that back at home the family was sitting around the dinner table, waiting to dig into my birthday cake. When we finally got out of the cave into the frigid February night, my winter jacket was soaking wet and I thought I would freeze solid. I'd lost the rope pads somewhere on the mountain, you see, so my coat had been "volunteered."

But that wasn't the worst trip, believe me.

Two weeks later I wrecked the car coming home from Limrock Blowing Cave and spent some quality time on the side of the highway, waiting for my father to arrive and ask why I'd taken the car out of town without permission in the first place. That might qualify as a bad caving trip, except that I don't remember the cave at all, just the wreck and its aftermath--so that isn't right, either.

I remember another birthday, my 22nd, spent at what was then Dripping Springs Cave (now an entrance to the Nunley Mountain system). Still weak from bronchitis, I pushed a breakdown choke into virgin trunk, only to sprain my ankle and be forced to exit the cave early with Richard Greer (who had received a concussion himself earlier in the day) while others scooped the cave. As Richard and I waited in the car, another member of the group got severely hypothermic hanging in a waterfall, and the resulting rescue--complete with video cameras and generators and a helicopter--closed the entire cove to cavers for decades.

Of course, there have been plenty of jagged crawls that ripped my knees and elbows, long cold hours surveying in muddy canyons, dead animals at the bottom of pits, all the usual horrors.

But naming the worst trip I ever had is easy.

The place was Mexico. The year was 1987.

We met the day after Christmas in Brownsville, Texas, crossed the border with all the customary hassles, and drove several hours south to Hotel Valles. According to the schedule, we were supposed to drop Hoya de Guaguas the next day, and Golondrinas the day after that. I had made arrangements for Bill Cuddington, who had been in the area just before Christmas, to leave the official letter of permission required to visit those caves at the hotel, but the desk clerk couldn't find the letter when we arrived.

We drove up to Hoya de Guaguas the next day anyway. The weather was lousy, foggy and cold. We all had visions of being arrested for doing the pit without permission. Hey, somebody said, it isn't far to the Pyramids, just a few inches on the map.

One of the big rules in Mexico is that you don't drive at night. Driving is dangerous enough during the day. You've got overloaded trucks and buses going 90 MPH, one-lane bridges, herds of goats and broken-down pickups parked around blind curves.

Hell-bent for the Great Pyramid, we made our way down incredibly twisting and turning roads over the mountains through dense fog. The sun went down. The road with its hairpin turns went on. We used CB radios to tell each other when it was clear to pass the dozens of slow-moving vehicles we encountered. As the hours wore on, we got more careless, and came within inches of a high-speed head-on collision.

Around midnight, thankful to be alive, we stumbled into a hotel in Pachuta.

Hell-bent for the Great Pyramid, we made our way down incredibly twisting and turning roads over the mountains through dense fog. The sun went down. The road with its hairpin turns went on. We used CB radios to tell each other when it was clear to pass the dozens of slow-moving vehicles we encountered. As the hours wore on, we got more careless, and came within inches of a high-speed head-on collision.

Around midnight, thankful to be alive, we stumbled into a hotel in Pachuta.

We were all low on gasoline, having long since emptied the extra containers we'd brought along. The Toyota was just a year old then, and I didn't want to foul the catalytic converter. A search for unleaded fuel consumed the entire next morning as we went from one PEMEX station to another. We eventually arrived at the Great Pyramid, still running on empty.

After a couple of hours of touring, one faction of the group was ready to depart. The other faction was drinking beer in the gift shop. Yet another bad decision was inexplicably made when several of us left in two vehicles to renew the search for gasoline, with plans to meet the next day at Rancho del Barro.

In addition to not driving at night, another good rule is to avoid, at all costs, driving in Mexico City. So into the city we went, cruising blindly in search of petrol all through the downtown. We did eventually find unleaded gas, but not until several near accidents in the busy traffic. Here, as elsewhere on our journey, it seemed that we were constantly being harassed by Mexican authorities. That bright red Toyota 4WD was a neon sign reading "Gringo." If a policeman was directing traffic, he would wave us to pull over. Whenever we saw the black and white car of the local Policia, it was certain that we were about to be stopped. Each time the drill was the same. I stood at the back of the truck while the officers indicated they just might want to search it. What they really wanted was a few American dollars. If they got it, they'd wave us gravely on. If not, they'd either search the vehicle or just keep me standing there for ten or fifteen minutes, hoping I'd get the point. Most of the time I gave them the money. It was faster that way.

(I hasten to add that for every time I've been extorted in Mexico, I've also encountered unsolicited kindness and generosity from others. By chance, however, on this particular trip the extortionists were outnumbering the Good Samaritans ten to one.)

On we went down additional foggy mountain roads, long into the night, pulling over occasionally for James, who was desperately stricken with diarrhea and vomiting, to run into the woods. We camped that night in the mountains not far from Rancho del Barro.

On we went down additional foggy mountain roads, long into the night, pulling over occasionally for James, who was desperately stricken with diarrhea and vomiting, to run into the woods. We camped that night in the mountains not far from Rancho del Barro.

The next morning we hired burros, carefully negotiating total round-trip payment in advance (a mistake, by the way), and managed to get all our gear and the 1,500 foot rope up to El Sotono. The group from the Pyramids arrived that afternoon, and we had the 1,200 foot drop rigged by dinnertime. While making the hike up to the pit, my knee--which I had injured a few weeks earlier--had blown out and I could barely walk. There would be no pitting for me. Another member of the team, Alice, had by now joined James on the sick roster. She wouldn't be doing the pit as planned, either.

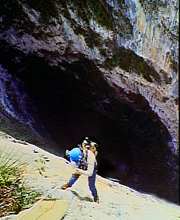

We had come a long, hard way to get ourselves and our equipment to the edge of the deepest pit in the world, but for most of us that was as far as we were going to get. In fact, as we found out the next morning, out of our entire group of ten, only two people were both able and willing to do the pit. I rigged a short rope over the long, sloping lip and photographed as Tim Farmer and Mike Moser each in turn slid past me, sank rapidly, and finally disappeared into the distance. They were back on the surface within the hour, and we had the rope derigged by Noon, a full day ahead of schedule. Now the group had their revenge upon me for leaving them at the Pyramid. Everyone hiked off the mountain, leaving Annie and me with the rope to wait for burros that weren't scheduled to come until the next day. I tried loading the 50 pounds of rope on my backpack, but only managed to move it 100 yards before the pain in my knee made me reconsider.

We had come a long, hard way to get ourselves and our equipment to the edge of the deepest pit in the world, but for most of us that was as far as we were going to get. In fact, as we found out the next morning, out of our entire group of ten, only two people were both able and willing to do the pit. I rigged a short rope over the long, sloping lip and photographed as Tim Farmer and Mike Moser each in turn slid past me, sank rapidly, and finally disappeared into the distance. They were back on the surface within the hour, and we had the rope derigged by Noon, a full day ahead of schedule. Now the group had their revenge upon me for leaving them at the Pyramid. Everyone hiked off the mountain, leaving Annie and me with the rope to wait for burros that weren't scheduled to come until the next day. I tried loading the 50 pounds of rope on my backpack, but only managed to move it 100 yards before the pain in my knee made me reconsider.

Annie and I had just lit a fire for the night when burros and two Mexican teenagers appeared out of the darkness. John, one of those who had gone down the mountain, had heroically searched the entire village of Rancho del Barro to find someone willing to come get us. Unfortunately, he'd done more than that. Although communication was limited by my poor Spanish, the Mexicans indicated that John had accompanied them up the mountain, but had fallen behind and was now somewhere in the woods. As we started down, I could hear John calling in the distance, far off the trail. Did he have a light, I asked the Mexicans. No, they said, no light.

Now I was faced with a real dilemma. I couldn't leave John up in the woods. I didn't entirely trust the young Mexicans and didn't want to leave them alone with our equipment. In fact, the burros were already out of sight, heading for home. I had a bad feeling about leaving the Mexican boys alone with Annie, but at the time that seemed the best choice. I would get John, then catch up as quickly as possible.

John was indeed lost in the woods and just about exhausted. With only my light between us, our progress was painfully slow. I soon realized there was no way we would catch up with Annie and the burros.

When the lights of Rancho Barro were finally in sight, I left John and limped ahead. Annie was okay, but my worst fears had almost been realized: One of the young Mexicans had flirted with her all the way down the mountain. However innocent his actions seemed to him (and I have no way of knowing how innocent they were), it was a terrifying experience for Annie.

But the day wasn't over quite yet. Our original burro driver showed up and demanded payment for his trip the next day, even though he had already been compensated in full for a trip he now didn't have to make. In no mood to argue, we simply got in our trucks and left. As we drove away, the man shouted that we should never come back, and at that moment I wanted nothing more than to keep that promise.

Another long drive in the darkness brought us to a hotel in Rio Verde. We went to bed without eating. When I awoke in the morning, my stomach still felt empty, but now I was nauseous. Suddenly I, a Mexico veteran who had bragged he knew the ropes and wouldn't get sick like the first-timers, had the dreaded tourista disease. We drove back to Hotel Valles, then decided to move to Hotel Tanninul. Having spent New Year's Eve at Hotel Valles in years past, I knew the party there would be loud and long. Tanninul would be a nice, quiet place to recuperate.

I will never forget that night I spent at Hotel Tanninul, sick enough to pray for death, trying in vain to sleep as a tremendous party went on in the lobby and the band played "La Bamba" for the 200th time.

Annie drove me home, all 2,000 miles. I remember a blur of motel rooms, sitting in a huge traffic jam at the border where an endless parade of Mexicans tried to sell us souvenirs, waiting for four hours in Brownsville to rendezvous with the rest of the group before finally giving up (we found out later that one of their trucks had been broken into and they had left soon after).

It was a journey of the damned. It was 4,000 or more miles, eleven days, hundreds of dollars spent, and the only cave I had experienced was a bottomless pit of nausea. It was the kind of trip where you make one mistake and then another and another and pretty soon you start thinking you'll be lucky just to get out alive.

It was the worst caving trip of my life, and when I looked back at the decisions that were made and the turns that we took, there wasn't anybody in the world to blame except myself.

Nearly a decade later, although I've learned a thing or two about prudent travel, I still can't help but cringe whenever I hear "La Bamba."

Photographs (in order of appearance):

Title Photo: Annie Ling near El Sotono, just before the arrival of the burros.

The Great Pyramid

The author and friends in Rancho Barro.

Tim Farmer on rope: 1,100 feet to go in El Sotono.

Water | Caving | Hang Gliding | Backpacking | About

Copyright © 1996-2013 by Rodger Ling.

All rights reserved.